Have I got a great story for you:

Have I got a great story for you:

A male narrator on a crowded bus witnesses a disagreement between a man with a long neck and a funny hat and a fellow passenger. The narrator then sees the same man a couple of hours later, this time getting some advice from a friend on how to add a button to his coat.

That’s it.

Ok, It’s not much of a story, I admit, but it’s nevertheless one that has had a profound effect on the way that I teach elements of my subject, in particular ideas of genre and perspective.

The plot – such as it is – comes from a neat little book written by Raymond Queneau in 1947 called Exercises in Style. Originally written in French and subsequently translated into over 30 different languages, Queneau’s book is a collection of 99 retellings of the same base story, known as ‘notation’, which I summarised above.

As the title suggests, each retelling is a writing exercise, where Queneau takes the original story and transforms it in accordance to a given literary or rhetorical style. And so we have versions such as double entry, where every detail and item is repeated and duplicated, or metaphorically, where the passengers on the bus are a ‘shoal of travelling sardines’ and the man doing the arguing is a ‘chicken with a long, featherless neck.’

I tend not to use Queneau’s exercises directly with students. Many of his retellings are too complicated and the rhetorical methods they are intended to illustrate are too advanced. I do, however, apply his approach, taking passages from stories and rewriting them from different perspectives and in different genres. It really helps to show how both fiction and non-fiction work and the importance of structure and viewpoint.

Transformational writing is nothing new. I’ve been teaching some form of recreational writing for years and students enjoy reimagining a missing scene, or transforming a passage from one genre into another. The exercises are different, though. Because they are so short, the focus of each is much more pronounced. The base ‘notation’ is also devoid of artifice, and so the core features of any stylistic or generic inflections are amplified.

In 2013 Bethany Brownholtz wrote a modern day extension to Exercises in Style as part of her Master’s programme. In her 21st Century Remix, Brownholtz draws upon styles that have emerged since Queaneau’s time, offering 40 variations on a new base story, which she calls the ‘gist’. As with Queaneau, the gist is not the focus, but rather the tone or genre that is applied to it.

Here is the gist in its entirety:

Commuter train to Chicago, early afternoon. Recurring cell phone dings. A middle-aged businessman plays with his phone. He sits across the aisle from a woman. She makes eye contact with the passenger in front of him—college kid, white undershirt, messy hair, like he slept on a futon. She smiles and rolls her eyes at the kid. A friendly gesture meant to commiserate. The kid shouts “What?” At the next stop, she apologizes and moves to another train car.

Thirty minutes later, the young woman uses the bathroom at Union Station. She notices an older homeless lady by the sink in distress and asks if she needs help. The lady requests that the young woman take the older lady’s pants off. The young woman says no and leaves.

Amongst Brownhltz’s re-workings are moods such as nostalgic and pissed off and contemporary styles such as memoir, rap and social media status updates. It’s a really useful resource, though I should stress I’m not advocating transforming literary works into rap lyrics or Tweets! This isn’t about making writing more engaging and relevant, it’s about making the art of the writing more explicit, such as the effects of different perspectives, styles and voices.

One activity I’ve undertaken recently with a year 8 writing unit is to explore the effect of different points of view on meaning – helping students to understand how the same story framed differently emphasises some ideas and attitudes, and downplays others.

The gist might look like this when inflected in the third person.

It was a cold October morning. Mrs James was travelling to London to make an early morning board meeting. The dusty grey train was packed with sleepy commuters, looking tired and bored. She had been lucky to grab a seat by the window, but just as she curled up in the corner to rest, a loud mobile phone ring brought her crashing back to her senses.

Or like this in the first person, from the point of view of the woman.

I was due at a board meeting at 9.00am in London. It had been years since I’d last got a train and I’d forgotten how crowded they got. Despite the fact that carriage was packed with commuters, I managed to find a seat by the window, next to an old lady and opposite a grumpy man in a suit. As I shut my tired eyes, the man’s phone suddenly burst into life!

Or even like this in the second person, where the reader becomes the woman.

You are heading to London for an important meeting with your clients. Last night was late and you are very tired this morning, barely able to keep your eyes open. You look around the carriage and spot a free seat by the window. As you nestle down in the corner, your sleep is interrupted by the sound of man’s phone and its annoying ringtone.

In each retelling something is gained and something is lost. Such a comparison of perspectives is arguably more effective at illustrating these differences than most verbal explanations. I guess it works in a similar way to the use of examples and non-examples when teaching difficult concepts. The key learning points are better understood through side by side comparison of getting it right and getting it wrong.

Hopefully you can see how this approach could be applied to other areas of the curriculum. For example, when reading a novel, a rewritten passage from a different perspective might help clarify authorial intent. Indeed, i’ve recently had some success with year 11 by making subtle changes to some of the source material on AQA Paper One. Understanding the perspective used by the writer and how the text is structured is quite tricky and comparing different narrative possibilities proved very useful.

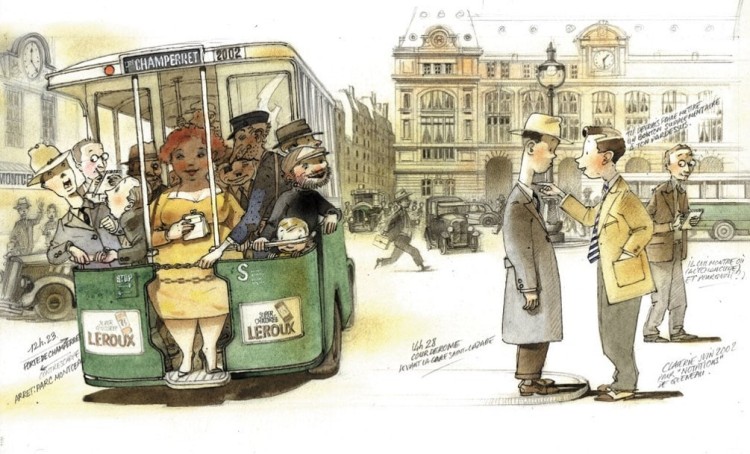

As with all stories, this is not the end. In 2005 artist Mark Hadden released Exercises in Style. 99 Ways to Tell a Story, a comic book rendering of Queneau’s work, in which Hadden applies the principles at work in the written form to the visual medium. In my next post, I hope to show how Hadden’s work has inspired my teaching, in particular at GCSE to explore how writers use structure to create meaning.

The end.

Or is it?